Back to the future

What happens if long bond and t-bill yields revert to historic norms?

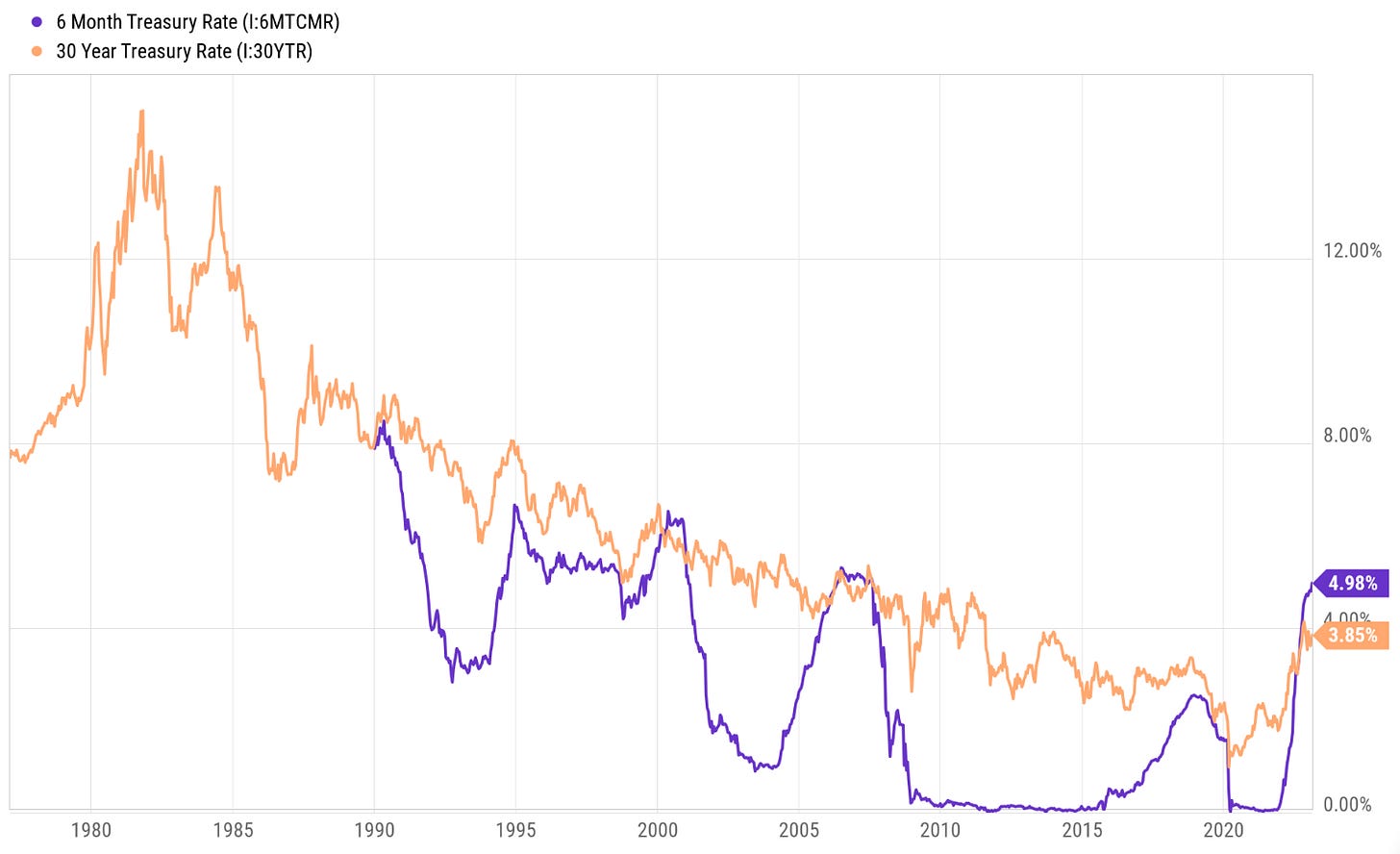

If you own stocks, bonds or a home, this is an important chart. You're looking at the yields on US Treasury 6 month bills (purple) and 30 year bonds (orange) over the last 30 years.

(To keep this readable, I've occasionally omitted some logic or terminology, though some of what's below is still arcane.)

U.S. interest rates, both long term and short, declined for forty years as investors gradually forgot the inflationary infernos of the 1970s.

Now short rates on US debt have jumped from ~0% to 5% (500 basis points) in one year as the Federal Reserve struggled to choke off inflation.

But debt investors with a longer time horizon currently believe a) that 2022's 7%+ inflation was temporary, sparked by stimulus, supply chain malfunctions and consumers' post-Covid splurging of money they'd saved while quarantining or gotten from the government and/or b) the world is headed into a recession.

Both of which make many investors think longer term bonds a currently good investment. So longer-term interest rates (for example, the US Treasury 30 year bond, known as the "long bond") have risen only 200 basis points from ~2% to 4%.

The result: yields on long bonds are now substantially lower than those on six month bills. Insiders call this an "inverted" yield curve. In crude terms, investors are betting that both short rates and longer rates will soon come down, so they want to lock in for the longer term current yields that will, in retrospect, look juicy.

But if you look at the chart below, you'll see how historically unique this inversion is. Long bond rates have historically hovered at or above short rates because investors generally want to get paid extra yield for the risk of lending money (whether to the government or businesses or home buyers) for a longer term.

This was particularly the case after the inflationary inferno of the 1970s. What idiot would lend money to the government at 5% for ten years if she or he might get repaid in dollars that, because of inflation, would be worth 7% less each year?

Which brings us to today. If the Fed or investors get spooked that inflation won't quickly return to the basement 0-2% levels of the last two decades and might even sometimes gyrate higher, then short rates might rise another 100-200 basis points. Which would certainly push yields on the long bond from the current 4% to 5-6%.

That jump would be bad, punishing current bond owners, burying homeowners and making stock returns, generally driven by anticipation of their ratio of price to future earnings, look miserly.

But there's a worse possible scenario-- traditional investors in long term debt might tire of waiting for inflation to come down to the <2% level everyone hopes for. Investors might notice that wages keep inflating as businesses try to fill jobs left open by retiring baby boomers, Covid mortality and disability, and capped immigration; that food prices tend to keep jumping because of heatflation; that energy prices remain prone to surging because of geopolitical friction; that supply chains remain wonky because of trade wars.

If (enough) investors give up on the dream that the dragon of inflation can be easily slain, longer rates might return to their historically more normal relation to short rates, floating 100-200 basis points above short rates.

To put it concretely, if you look closely at the graph below, you'll see that the last time 6 month rates were at 5% in 2005, long bonds were also at 5%, which is to say 100 basis points cheaper than current levels. And the time before that, in 1995, long bond yields were around 7%.

Which means that, even if short rates don't rise, long bond prices could fall 15-30% from these levels, pushing the stock market down even more severely and driving mortgage rates to 8-9%.

In a worst case scenario, short rates could rise to 6% and the curve could steepen from the current -100 basis points to +100 basis points, putting long bond yields at 8%. Which would in turn drive mortgage rates to 10%. And price earnings ratios, currently at 22, would fall to 10 or 12, putting stock prices 50% lower than today.

Don't worry, if any of this happens, it won't transpire in days or weeks.

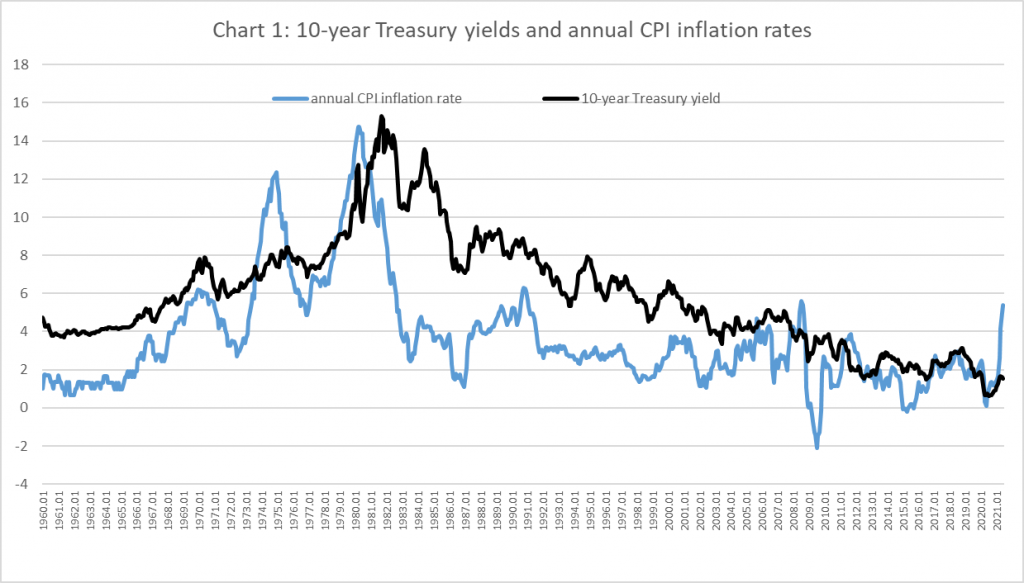

Adjustments in investor attitudes and expectations will be a long, slow grind, a reckoning played out over the course of years. You’ll notice in the graph of CPI and inflation that as inflation surged in the sixties and seventies, it sometimes took bond yields years to catch on/up. The same lag held true as inflation declined. Investors are human, content to live in the past, slow to wake up to uncomfortable new realities, eager to hang out with peers who endorse their own dreams of a simpler, better era.

(Speaking of the past, I should admit my own biases. I lived, breathed and earned in the US Treasury market in NYC and London 1984-1991. My synapses are imprinted with the high yields of that period. We all have inflation PTSD. I still can't really shake our collective habit of looking over our shoulders at the 1970s as we tried to prognosticate how low rates might go. They went a lot lower than any of us expected!)